RSV (respiratory syncytial virus infection) is one of the dozens of viruses that can cause “the common cold.”

But it’s one to watch out for: it’s highly contagious and unlike some of the other common cold causes, RSV can turn dangerous. Preemies, infants, young children; people with immune, lung, or heart disease; and older adults are at risk. And RSV is having a *moment* in the Northern hemisphere right now.

My kids went to a rock climbing camp two weeks ago. It was our first in-person indoor group activity since March 2020. Masks were required, but nonetheless, they immediately caught colds, which they immediately gave to me and my husband.

Fortunately for us, everyone got better within a few days. We were sick, but not seriously ill. I don’t know if we had RSV, because no one was sick enough to warrant a trip to the doctor. This is the typical RSV pattern. We avoided any interaction with the grandparents while we were sick just in case, especially since one of the grandparents is in a high-risk group. Though RSV is very often thought of as a kids’ health problem, it causes more than 150,000 hospitalizations and 14,000 deaths among *older* adults in a typical season.

RSV is normally a seasonal virus with an epidemic curve that gets going in mid-September just after kids go back to school. The seasonality is likely driven by its transmission mode: RSV is spread by snotty fingers touching shared surfaces and by coughing and sneezing in shared indoor air. In fact, by age 2, nearly all children will have had RSV at least once, and half of children will have already had it twice. RSV infection doesn’t produce good immune memory, so we can get it again and again. Each time we get it our immunity builds a little bit, so older children and healthy adults get less severe disease on their 5th, 6th, 12th, or 40th go with RSV.

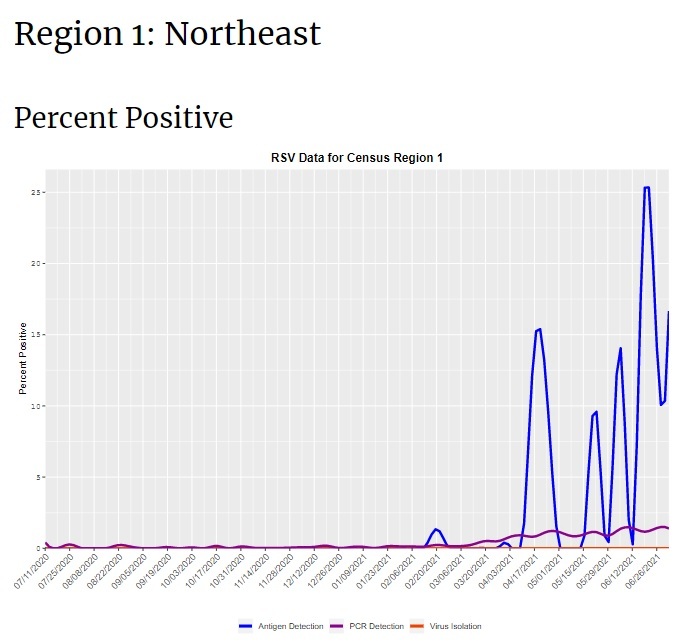

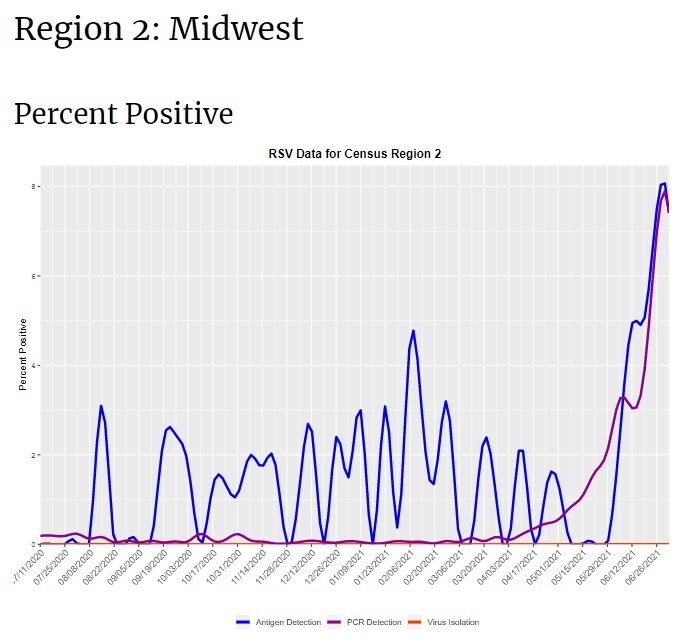

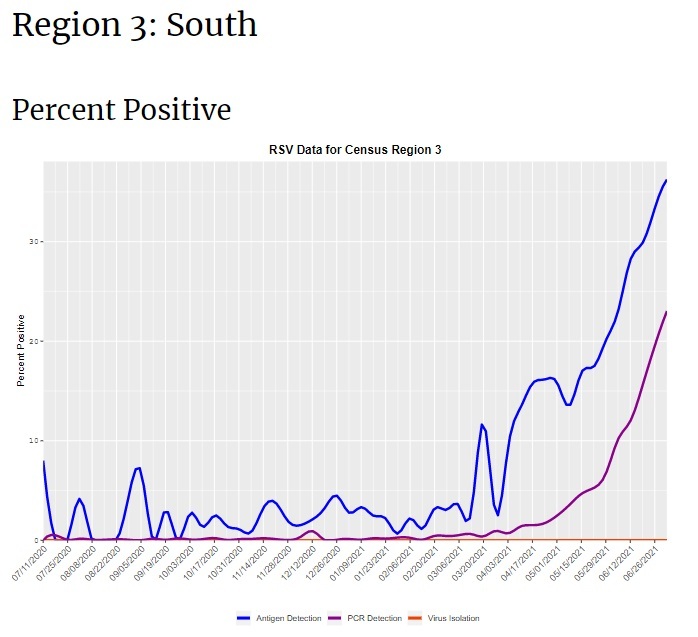

This year, the Northern hemisphere is having a very unusual ‘summer spike’ of RSV, likely because kids have suddenly started gathering for in-person activities for the first time in more than a year. This could also be “catch-up” from the missed normal RSV season last winter. RSV is something all people get eventually, so if you have a toddler who didn’t get it last winter, you’re overdue. In June, CDC issued a notice warning clinicians about an RSV outbreak in southern states. At this point, not too much is happening in the Western states, but there is a major outbreak ongoing in the South, Midwest, and Northeast US. Note that there’s not a lot of routine testing for RSV, so the data are a little spotty. CDC RSV Census Regional Trends

RSV causes a lot of serious illness every year. It normally causes more than 2 million doctor’s visits in kids under age 5, and more than 200,000 hospitalizations in the United States every year–most of these among older people. And in a typical season, RSV kills 14,000 older, high-risk adults.

Symptoms of RSV appear 4-6 days after you’ve been exposed, and usually include: runny nose, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever, and wheezing. These symptoms usually appear in stages, so it’s like every day is a new adventure in feeling cruddy for about a week. In newborns, the only symptoms may be irritability and breathing difficulties. In kids, it’s usually a runny nose and decreased appetite followed by a cough a few days later. In adults, it is often indistinguishable from any other cold.

Most people get better on their own, but in a few people it can cause serious inflammation of the lungs and pneumonia (an infection of the lungs). It can also cause dehydration. These more serious cases can require hospital care.

The prevention for RSV is old-fashioned: keep your hands clean and avoid close contact with people who are sick. In this case, “close contact” means kissing, shaking hands, and sharing cups and eating utensils.

If you have symptoms of “the common cold,” avoid contact with people who are high-risk like newborns, preemies, people with compromised immune systems, and people who have chronic lung or heart disease. You’re no longer contagious within about a week of symptoms appearing. CDC Link

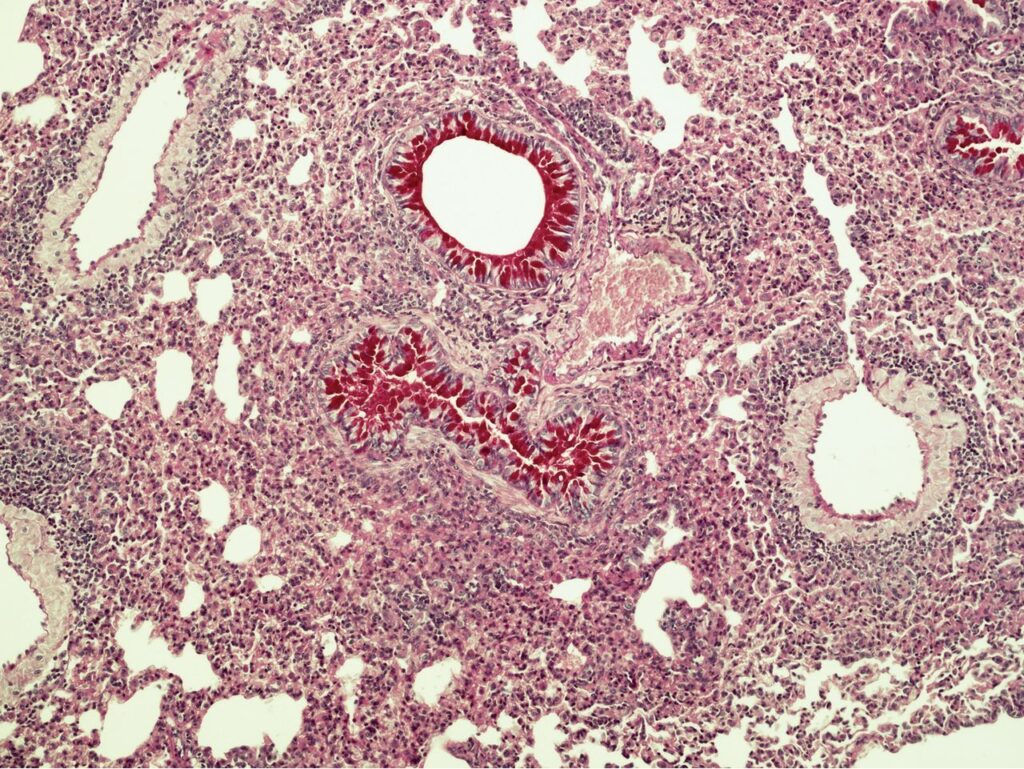

Scientists have been working on a vaccine for RSV for decades, so far without success. An investigational vaccine candidate failed hard in 1967 after it was found to make subsequent RSV infection worse in young children. Two toddlers died of severe RSV after receiving the vaccine, and hospitalization rates were extremely high. It’s probably the most spectacular vaccine failure in history. This is the first known example of “vaccine-associated disease enhancement.” Worries about repeating this mistake are still top-of-mind whenever scientists develop a new vaccine, and vaccine candidates are monitored carefully for any signal that vaccine-associated disease enhancement is at play.

Developing a vaccine for RSV has been haunted by this failure. For a long time, it wasn’t even considered an option. The causes of the problem took decades to untangle, and no one wanted to risk repeating the same mistake until the cause was understood.

However, more recently, the tremendous burden of RSV and improved understanding of the disease process has sparked renewed interest. It’s a tricky one to design a vaccine for, in part because we’d want to protect newborns whose little immune systems don’t mount a strong immune response. One strategy under consideration is vaccinating people during pregnancy. We know that RSV antibodies are passed to the baby in utero. (Antibodies are also passed to the baby in breast milk.)

Another strategy is to design a vaccine to protect only older adults (who did not have vaccine-enhanced disease in the failed trial from the 1960’s–it only happened to people who had never had RSV before).

But, so far no other vaccine candidates have been successful in trials. There is hope that the latest in vaccine tech–the same technologies that brought us COVID-19 vaccines–could also mean a breakthrough for this persistent problem. AstraZeneca and Sanofi recently announced a successful Phase III trial of a new treatment (not actually a vaccine, but rather a long-acting prophylactic antibody).

For now, we’re stuck with plain old handwashing, coughing in our elbows, and canceling plans with grandmas and newborns because we have runny noses.

American Society for Microbiology on RSV

Lung section of a mouse with vaccine-associated enhanced RSV disease from American Society for Microbiology on RSV