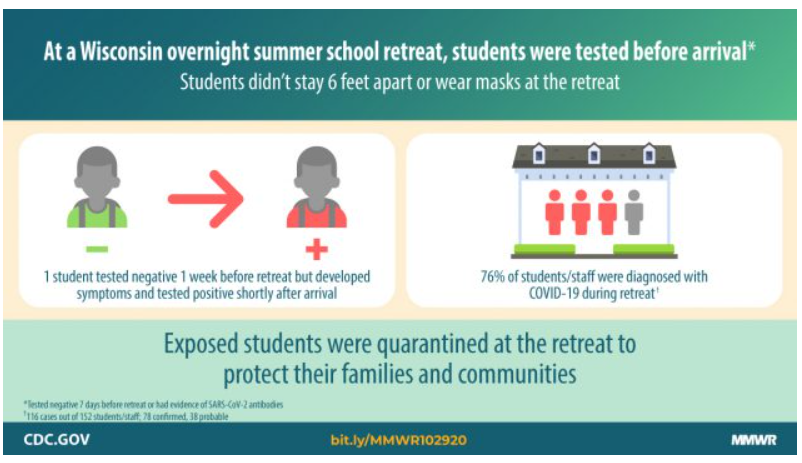

A: Retreat organizers relied primarily on a test-based strategy for preventing individuals with COVID-19 from attending the retreat and didn’t employ other measures to prevent transmission of COVID-19 among attendees.

This did not work. Consequently, a single attendee who became ill the day after arriving led to 116 other attendees (76% of attendees) becoming a case of COVID-19.

What does a test-based strategy mean exactly?

Retreat attendees traveled to the retreat from 21 states and territories and 2 countries. Attendees were required to provide proof of a negative PCR-based test (i.e., test that identifies genetic material from the SARS-CoV-2 virus) ≤ 7 days before travel or documentation of a positive serology test (i.e., test that identifies antibodies indicative of past infection) within the past 3 months. Households in which attendees lived were also instructed to self-quarantine for 7 days before travel and to wear masks during travel. Students and counselors were not required to wear masks or social distance and were allowed to mix freely at the retreat. While classes were held outdoors, attendees roomed together indoors in dorms or yurts. In other words, they tried to rely primarily on attendees testing negative before arriving to prevent transmission at the retreat

Why didn’t this strategy work?

It can take 2-14 days for someone who is exposed to SARS-CoV-2 to develop symptoms of COVID-19. It is recommended that individuals wait until ~4-5 days after being exposed to a case of COVID-19 to get tested as before this point, as before this the false negative rate is high. Assuming the attendee who became ill the day after arrival to the retreat did quarantine for the 7 days before traveling to the retreat, they could have unknowingly been exposed to someone with COVID-19 eight or more days before departing for the retreat and become infected, but on the day they got tested (sometime in the week before departing), the virus had not yet replicated enough to be detected via a PCR-based test. It is also possible they were exposed while traveling to the retreat and developed symptoms quickly thereafter. Indeed, if attendees of the retreat broke quarantine to travel, this eliminated any potential benefit of having engaged in a 7-day quarantine period, which given the incubation period of 14 days for this virus, was really not adequate to begin with (see more on this below).

The second way a test-based strategy failed in this situation, was that it was used to try to stop further spread of the infection from the first case to other attendees. After the initial case was isolated, 11 of the individual’s close contacts were quarantined, but then released from quarantine after only a few days because they received negative test results using a rapid antigen-based test (i.e., test that identifies proteins on the surface of the virus). CDC recommends individuals who are a close contact to a case of COVID-19 quarantine for 14 days (i.e., the full incubation period), regardless of whether they receive a negative test result. Again, this is because of the possibility of a false negative test result, when testing occurs too early in the incubation period. False negative results are of particular concern with rapid antigen-based tests, which are not necessarily designed to screen asymptomatic individuals. Six of these 11 attendees went on to develop symptoms as did 18 other attendees without known history of exposure to COVID-19. These attendees were given masks, but no contact tracing was carried out and these students were not isolated. In the end, 116 individuals attending the retreat ended up contracting COVID-19.

What are the implications of this?

***If you aren’t sure IF or WHEN you were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, it is really hard to know whether you are getting tested at the right time during the 14-day incubation period for SARS-CoV-2, to detect that you are positive. Even if you do know when you were exposed to a case of COVID-19, CDC recommends that exposed individuals quarantine for 14 days, regardless of getting a negative test. In either scenario, if you have been infected, you could test negative but then start to spread COVID-19 to others beginning ~2 days before your own symptoms start. This makes treating a negative test as a free pass to not adhere to #SMART guidelines (S-space, at least 6 feet, M-mask, A-air, outdoors or well-ventilated, R-restrict, small group size, T-time, short duration) risky.***

When CAN I trust a negative test result?

If you have self-quarantined for 14 days, don’t develop symptoms of COVID-19 and then get a negative PCR-based test, you can be very confident that you do not have COVID-19. You have made it past the 14 day incubation period during which symptoms typically develop and tested negative for COVID-19 well after the point in which the virus would have replicated to sufficient levels to be detected on this type of test. Similarly, if you get tested and get a negative test result and then quarantine for 14 days and don’t develop symptoms, it is unlikely that you are infected.

Outside of these scenarios, a negative test is unfortunately just not a guarantee that you aren’t infected with SARS-CoV-2 and can’t spread it to others.

As we think ahead to the upcoming Thanksgiving holiday and potentially getting together with family or friends, we should NOT be thinking about testing as a free pass to skip other precautions. Indeed, the safest route to getting together is for everyone who plans to gather, to quarantine for 14 days ahead of time with no opportunity for exposure during travel to the gathering [THIS MEANS STARTING TO QUARANTINE ON FRIDAY NOVEMBER 13TH]. See our previous post on this which includes a handy timeline and several examples of how a test-only strategy can go awry.

CDC report on this retreat outbreak

More information on the limitations of a test-based strategy

And our prior post on how a test-only strategy didn’t work in the White House