This information is up to date as of September 16th, 2024 at 2 pm EDT.

Pandemic potential remains low despite 14 cases* of H5N1 in humans for 2024, but the situation is still evolving.

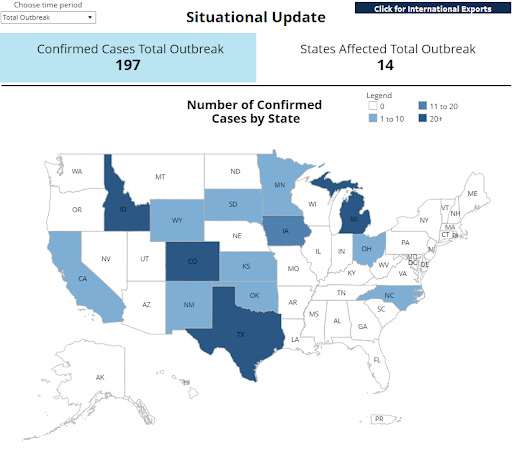

Cattle infected with H5N1 now spread across 14 states, with 4 human cases from cows, 10 cases from poultry (9 in 2024, 1 in 2022), and one case with no immediately known animal exposure (Missouri)*. The threat of disease to humans without contact with cattle or wild birds remains low.

*10 confirmed as H5N1; 5 are H5 with unknown N subtype, thought to be H5N1

HPAI Confirmed Cases in Livestock | Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (usda.gov)

H5N1 Recap:

- Traditional H5N1 human vaccines are available in limited supply

- H5N1 human mRNA vaccines are in Phase I trials

- Antivirals are available

- Beef likely has the same safety profile as pre-outbreak (follow safe cooking guidelines, as always)

- Pasteurized milk is safe

- Raw milk could contain live virus (in addition to bacteria) that could make you sick

- PPE is recommended and being provided free to farms, but not all farms are participating

- National restrictions on dairy cow movement are in place, with some states enacting stricter recommendations

What’s new:

- CA reported its first cases of H5N1 in dairy cattle, although this is not surprising because it was detected in CA wastewater as early as June

- CDC now has a H5 dashboard, but Stanford’s Wastewater SCAN dashboard continues to be more comprehensive

- USDA is funding trials of H5N1 vaccine in cattle

- Starting 9/16/24, the USDA will be routinely testing beef for slaughter for H5N1

- Blood studies of 35 dairy workers on two Michigan farms with infected cattle showed no antibodies against H5N1, meaning there is no evidence of asymptomatic spread among humans (asymptomatic spread is worrisome because it is difficult to track and control)

The Johns Hopkins University Center for Outbreak Response Innovation (CORI) assesses the general risk to the public as low. Outbreaks are considered “low” risk if there is very low or no human-to-human transmission, but there is potential for the virus to adapt to humans.

Currently there is no evidence of human-to-human transmission. Both the confirmed case in Missouri and their household contact developed respiratory symptoms on the same day, which makes transmission between the two highly unlikely (we would expect someone to get sick 3-5 days after contact). It’s more likely that these two people became ill from the same (unknown) source. The household contact had a mild illness but could not be tested with a nose swab for flu because they had already recovered. Blood tests can be done to test for flu antibodies, but, understandably, not everyone agrees to giving a sample.

Unlike the other human cases this year, this confirmed case had more severe disease (hospitalized but not critical illness) and no known animal contact. We know they had some medical conditions that put them at increased risk for severe illness and complained of chest pain. Flu screening is typically only done during flu season (fall/winter), but the CDC recommended clinicians continue to screen during the summer, which is why the sample was tested.

Almost every year, a handful of people become ill with animal-type flu without known contact with pigs or other agricultural animals. Although human-to-human transmission is a possibility in these cases, we have no direct evidence that this has happened. We do have evidence that no animal-to-human cases of flu have led to a pandemic since the 2009 “swine” flu.

While the early days of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic began with cases of people without known animal contact, H1N1 is a strain of flu better adapted to human hosts than H5N1. Paul Offit recently summarized why the H5 strain is low risk for causing a pandemic, despite periodic human infections since the late 1990s. In the past 100 years, the H5 strain has never caused a pandemic in humans.

This doesn’t mean that an H5 strain can never cause a pandemic. Since cows have receptors for both H5N1 and H1N1 in their udders, one concern is that a cow co-infected with both strains could enable the viruses to swap genes and create a new strain that is more transmissible in humans. To reduce this risk, the USDA has begun an H5N1 vaccine trial for dairy cows.

While the USDA focuses on curbing the spread of bird flu in cattle, we can do our part by staying home when sick, getting vaccinated against (human) flu, and encouraging others to do the same. The less (human) flu that is going around this season, the less likely a person will pass it on to cattle and create the conditions for a worst-case-scenario.

Stay safe. Stay well.

Those Nerdy Girls

Previous Bird Flu Updates: