Should I get a water filter to remove PFAS from my water? Which type is best?

Water filters are a wise investment if your tap water has potentially harmful levels of PFAS (a type of “forever chemical”). Roughly 5-10% of public water supplies in the United States have elevated PFAS levels (above the US EPA limits). The other 90-95% have either no PFAS or such low levels that reducing them further won’t impact our health. The best way to remove PFAS at home is with a reverse-osmosis system under the sink.

Around the world, health and safety regulators are setting limits for levels of PFAS in our drinking water – such as the regulations announced in April 2024 by the US EPA. These regulations help protect us from consuming harmful levels of these “forever chemicals”.

PFAS 101: PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a group of “forever chemicals” used to make a wide range of products that resist heat, water, and grease. They’re in non-stick cookware (e.g.Teflon), stainguards (e.g. Scotchgard), food packaging, firefighting foams, and much more. Learn about PFAS and their potential health impacts in this Nerdy Girls post.

Does my water have unsafe levels of PFAS?

There’s a good chance that your drinking water contains trace amounts of PFAS, but this is not necessarily cause for alarm. When we talk about PFAS – or any chemical – and our health, we need to consider the level. As we are fond of saying: the dose makes the poison!

A recent study by the United States (US) Geological Survey reported that roughly half of US tap water supplies are contaminated with PFAS. Fortunately, the situation isn’t as dire as it seems, and levels of these chemicals were typically very low (below the strict new US EPA limits). Roughly 5% (1 in 20) of tap water supplies had concerning levels of one or more types of PFAS (e.g. PFOS or PFOA). This study included 716 tap water supplies (269 private-well; 447 public supply) across the US, from residences, businesses, and drinking-water treatment plants.

A larger study of drinking water contaminants by the US EPA had similar findings. Roughly 10% (1 in 10) of public water supplies tested (293 of 2883) had concerning levels of one or more types of PFAS – the other 90% either had no detectable PFAS, or extremely low levels (below the new US limits). Using a health and safety limit called “hazard index”, which combines the results of various PFAS types, a small fraction of public water samples (0.7% or 1 in 142) were deemed concerning.

In both nationwide studies, higher levels of PFAS contamination was more likely in certain regions, due to manufacturing and use.

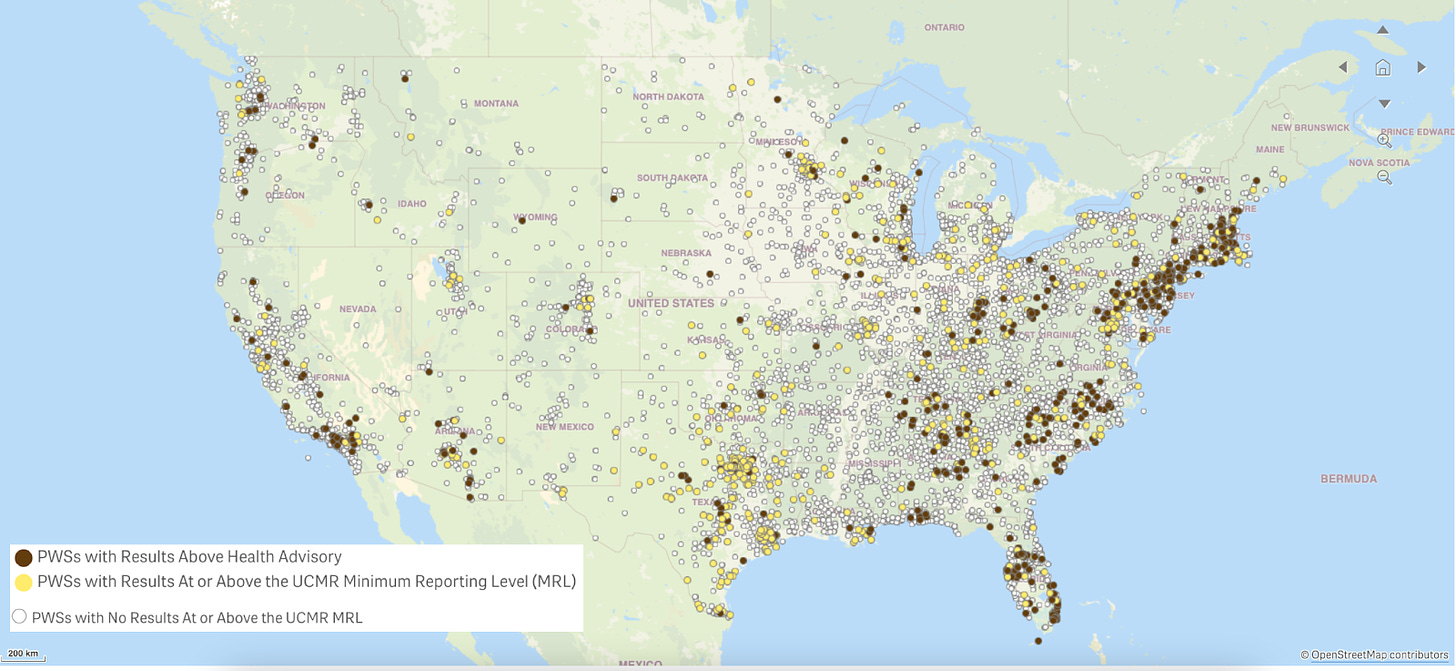

PFAS levels in public water supplies (PWS) in the United States. White = Below detection limit; Yellow = Detectable; Red = Greater than health limits. MRL = Minimum Reporting Level. Source: PFAS Analytics map with data from US EPA.

In Canada, and in Europe it’s a similar situation: PFAS are commonly detected in drinking water but usually at levels that are below the safe limits, with a lot of regional variation.

Note: Each country’s limits for PFAS levels in drinking water are different (see US Environmental Protection Agency, Health Canada, Europe). Why? Because we don’t know enough to precisely define the limit. In general, limits are becoming stricter, and the most recent US EPA drinking water limits are well below those in most other countries.

How can I find out the PFAS levels in my water?

- Pay for PFAS water testing. The most direct way to find out the PFAS levels in your water is to pay a certified lab for testing. Unfortunately, this is expensive: typically costing $300 or more – which isn’t far off from the price of some water filters! Testing labs should be able to help you put your results in context (i.e., “Is this level too high?”).

- Contact your municipality. Before you shell out for testing, see if you can get your hands on municipal testing reports. PFAS testing and reporting varies from place to place and may require some sleuthing. I live in Vancouver, Canada and it took me some digging to find this report. I was thrilled to see that PFAS levels were well below the most conservative limits, which stopped me from paying for testing or installing a filter.

- Use contamination maps. There are several interactive dashboards showing known PFAS contamination in the United States and around the world. The US Government dashboard shows tap water contamination across the US and this PFAS Project dashboard shows a broader set of contamination sites. Some states also offer their own PFAS contamination map dashboards (e.g. Michigan, New Hampshire, Washington State and more). When using dashboards, pay attention to the filters and focus on contamination sites with levels above safe limits (detectable does not always mean harmful!). Maps of PFAS contamination sites maps are also available in Europe, Canada and elsewhere.

- Educate yourself about PFAS “hotspots”. Certain areas are more likely to have high levels of PFAS contamination. PFAS “hot spots” include some factories, military bases, airports (especially military airports and firefighting training areas where AFFF (aqueous film-forming foam) is used), wastewater treatment plants, and farms where sewage sludge is used for fertilizer, landfills, or incinerators. Places that are downstream of these “hot spots” are also at higher risk of elevated PFAS levels. Learn more about high-risk areas in this Nerdy Girls post.

Note: Taking control of PFAS levels in your water is especially important if you have a private residential well, as you are responsible for testing and filtration!

Which water filter is best for removing PFAS at home?

To remove PFAS from tap water at home, you’ll need to invest in a water treatment system, costing a few hundred to a thousand dollars. Each of the three main technologies has a range of performance depending on the type of PFAS (short chain PFAS vs long chain PFAS vs GenX), the condition of the water being treated, where it’s installed, maintenance status, and more.

- Reverse osmosis: This is the most effective option for removing PFAS. In real-world studies, reverse osmosis systems removed virtually all short chain and long chain PFAS (88-100%) and most GenX PFAS (75-99%). These filters are typically installed under the sink, either with or without a tank.

- Activated carbon: These popular filters are moderately effective at removing PFAS. In real-world conditions, fridge systems remove 29-78% of PFAS (performance is lowest for short chain PFAS). They can be installed in a whole-house system or in fridges, faucets, or under the sink (note: pitchers with filters won’t get the job done because the water passes through so quickly).

- Ion exchange. Certain types of ion exchange filters (anion exchange) remove PFAS very well (>75% removal), in lab studies. Data on real-world home performance are limited, but it’s safe to assume that this is a reliable method. Ion exchange resins are often used for whole-house filters but can also be installed under the sink.

When choosing a system, ensure that it’s certified to remove PFOA and PFOS (two key types of PFAS). Look for NSF/American National Standards Institute (NSF/ANSI) 53 or NSF/ANSI 58 certified in the product specifications and as a search term.

Finally, be sure to consider practical factors like cost, space, and maintenance requirements. While reverse osmosis systems are best for PFAS removal, they are more expensive ($200-$600 or more for under-the-sink systems), less compact, and require more maintenance than other options. Water filter systems also vary in how well they remove other contaminants, like bacteria, viruses, and minerals (note: removing all minerals is not necessarily a good thing and remineralization may be needed).

Related posts

- Who is most exposed to PFAS (forever chemicals)? — Those Nerdy Girls

- How do PFAS (forever chemicals) affect my health? — Those Nerdy Girlsl

Resources & References

- Water Filters Fact Sheet – US EPA

- Water talk: PFOS, PFOA and other PFAS in drinking water – Health Canada

- Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in drinking water – US EPA

- Treatment of drinking water to remove PFAS – European Environment Agency

- PFAS Risk Assessment – European Environment Agency