By Malia Jones

Dec 11, 2020

The first time I heard of the new coronavirus circulating in China was in late January 2020. I was auditing Dr. Ajay Sethi’s course, Infectious Disease Epidemiology, at UW-Madison that semester. One afternoon in January before class started, Ajay casually asked the class: “How many of you have heard about the new virus in China?”

In mid-February, my husband and I headed out on a long-awaited, no-kids, two-week vacation to Iceland. Upon landing in Iceland, we received automated texts from the Iceland public health service with instructions about symptoms and services for COVID-19. We went to Iceland in the middle of February in order to see the northern lights. We did see the northern lights. I had *no idea* what we were getting into with island-in-the-middle-of-the-northern-Atlantic weather. Coming from Wisconsin, I thought I knew winter; but winter in Iceland is truly something else. I didn’t anticipate the wind. 2020 has been full of surprises.

Airbnb In Iceland

By this time, the situation in China was looking really bad, and South Korea had an outbreak too. Then, between February 22 and 27, I watched with growing horror as Iran, Italy, Spain, France, Germany, and the UK all confirmed their first cases. I studied my phone each evening, checking the Promed updates and trying to figure out if the case growth looked exponential. I tried to order some N95 masks from Amazon to be delivered back home, but they were already sold out.

And then the United States confirmed a cluster of cases in Washington. The WHO wouldn’t officially declare COVID-19 a pandemic until March 11, but it was obvious already that we had a really big, really global problem. It was SARS, but not successfully contained. I knew it would be bad.

When I imagined what was coming, I thought of being in lockdown. But the lockdown I imagined was a fantasy. I imagined all the spare time I would have. I thought of cozy fires and novels. I bought tons of yarn. I planned to knit my whole family Icelandic style sweaters.

I had no idea how bad. I really didn’t. When I imagined what was coming, I thought of being in lockdown. But the lockdown I imagined was a fantasy. I imagined all the spare time I would have. I thought of cozy fires and novels. I bought tons of yarn. I planned to knit my whole family Icelandic style sweaters. If you’ve ever seen me on a zoom call, that’s the yarn in the background.

I thought it would last a few weeks. Six weeks at the most.

On February 28, Iceland identified its first case. We were due to fly home the next day. I wondered if we should get out of there a day early. There were no flights available. We departed on February 29. The overnight flight was lightly populated and went smoothly. We arrived in Chicago O’Hare, where the customs scene was a complete horror show of infectious disease prevention. By this time, masks were sold out everywhere, and no one was wearing one. Hundreds — maybe thousands — of people were packed in the switchback line to go through customs for over an hour. No one screened us for symptoms. No one asked questions about whether we had been in Italy or China.

I remember seeing a folding table off to the side staffed by CDC. They had three people waiting in chairs, looking feverish and miserable; one was wearing a surgical mask. One was wearing a face shield. And one was, inexplicably, wearing a pair of costume steampunk flight goggles. That was probably my first real WTF moment. Customs staff were exceptionally rude that day, and the lines were exceptionally chaotic. The air felt moist. It was crowded. Babies were crying. It was nightmarish. Thinking back on it makes the hairs on my arms stand up.

Upon escaping customs, I went straight to the airport bathroom and scrubbed my hands and face. I scrubbed up to my elbows like I was going into surgery. My husband put hand sanitizer on every part of his exposed skin. We rode the bus home. I didn’t find time to unpack my bags until weeks later.

Like many people in the United States, I woke up on Monday, March 2, 2020 to a world in crisis. The state of Washington was at the beginning of what looked to be a major outbreak, the first in the United States. Every time I had ever heard about the SARS pandemic, it was followed quickly with the comforting words “successfully contained.” Now, a highly infectious and novel virus related to SARS was already spreading across at least five continents. And it seemed that no one had any idea what was going on. It was my first day back from vacation.

Before COVID-19, I didn’t study pandemics. I didn’t study novel viruses. In fact, up until March of 2020, I studied old viruses — the ones that have been around long enough to have well-established childhood vaccination programs. The ones whose vaccination programs have been around so long that they’re starting to lose their punch in part because people have forgotten what it’s like to live with infectious disease.

Specifically, I studied (and still do study) how vaccinating a population protects us from outbreaks through the statistical phenomenon called herd immunity, which is by definition the opposite of an immunologically naive population (that is to say, a population with no immune people at all).

I study how the contact patterns of human beings — the paths we scribe as we move from our homes to schools to soccer practice to places of worship — come together in a complex dance. These patterns are the foundation of how infectious disease spreads, and they are conditioned on social factors like segregation, poverty, employment, age, gender, and many more.

And more specifically, I study how the contact patterns of human beings — the paths we scribe as we move from our homes to schools to soccer practice to places of worship — come together in a complex dance. These patterns are the foundation of how infectious disease spreads, and they are conditioned on social factors like segregation, poverty, employment, age, gender, and many more.

That last part — the patterns we trace, the intersection of infection and the spaces we inhabit, is what led me here. To co-founding a social media platform called Dear Pandemic.

My expectation, at this point in early March, was that emergency pandemic response plans would be triggered. That my great country would direct its resources at this challenge, and win. Quickly. It was clear that there was a problem with not enough testing, but having seen testing ramp up in China, South Korea, Italy, France, Germany, and to some degree, Iran, I fully expected that testing would be coming online in volume by the end of that week.

I started getting questions from people I knew. At that time, most of the questions were about whether to cancel Spring Break plans. Which seems almost funny in retrospect (almost). On Thursday morning, March 5th, I woke up early and wrote a long email to my friends and family about what I saw going on. I included lots of practical advice for what was coming next–basic terminology, cancelling upcoming trips, the possibility of school closures, what the recommendation was about wearing masks.

Some of the things in that email turned out, in retrospect, to be wrong (most especially the heavy emphasis on cleaning surfaces). And a lot of it turned out to be right. At that point, no one knew anything, so a lot of my email recipients were grateful to have some advice that seemed calm, informed, and practical. People forwarded it. The email quickly went viral. It got forwarded all around my personal network and far, far beyond. Someone–I don’t remember who, unfortunately, because this really is ALL their fault–asked me to put it on Facebook, which I did. In a matter of hours, it had been shared hundreds of times. By Saturday morning, it had been shared hundreds of thousands of times, and the beleaguered google doc hosting it was regularly freezing due to too much traffic.

I started getting messages from friends that someone with no connection to me had reforwarded my message back to them, or that it was spotted in the wild by a friend’s mom. Ultimately, the email was picked up and published as an opinion piece in USA TODAY.

USA TODAY, March 13-15 Weekend Edition

More people sent me emails. They emailed asking about infectious disease. About risk. About risk factors. About kids, adults, grandmas, teachers, mothers, and dogs. My email was flooded with people asking specific questions and medical advice. Sometimes they said I was a lunatic. Some of the people were themselves acting like lunatics. People emailed angry comments (specifically about the mask advice–already a touchpoint). Someone sent me a clipping from a Michael Chriton book as evidence that the virus was made in a lab. Someone sent me an email suggesting that I talk to my astronomy department and attaching some star charts.

I did not talk to the astronomy department.

Mostly, people wrote just saying thank you for providing some sane advice. There was truly a vacuum of information, and I was getting sucked into it.

Alison Buttenheim, long a collaborator of mine in the vaccine research space, shared the post and reached out to me. She was also taking a lot of queries and making public posts on her Facebook page. Her department at Penn had asked her to take point on media inquiries about the virus. We joked about our newfound “fame.” A mutual acquaintance posted that whatever else he was hearing, he was going to listen to those nerdy girls — Alison and Malia. We laughed that Dr. Oz would be calling next

That’s when Dr. Phil called.

The next week, while I was taping Dr. Phil, Ashley Ritter, PhD — a Penn colleague of Alison’s — suggested that we put our messages on a public page. I agreed, and before we knew it, Alison had set up the Instagram page. The Facebook page followed soon after, and Alison set about inviting other nerdy girls to help. As a team, we started sharing updates. I can’t remember who invited whom or what we asked them to do originally. We were just looking to pull in the people in our network who were smart and sharing good intel on social media, with a general audience in mind.

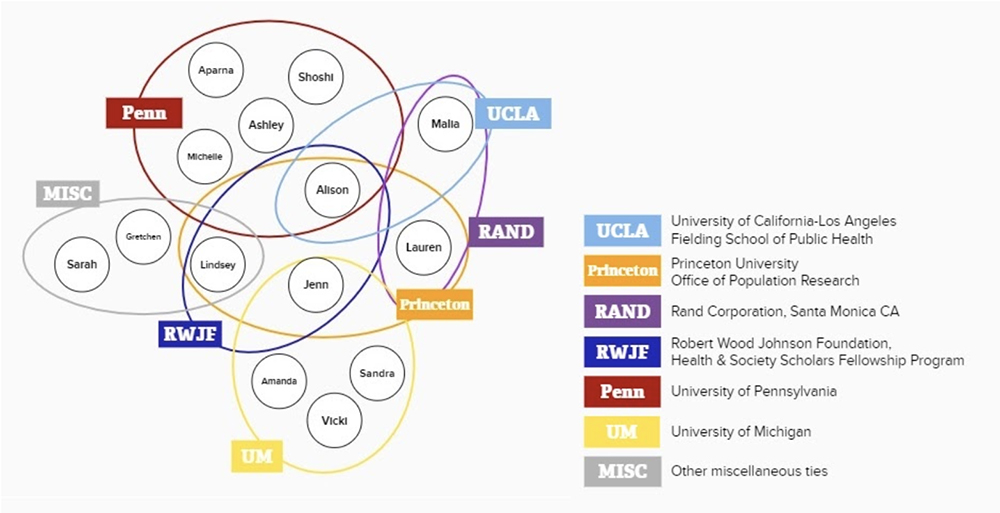

By the end of March, our team included 10 PhD-trained women: Malia Jones, Alison Buttenheim, Ashley Ritter, Shohi Aronowitz, Aparna Kumar, Amanda Simanek, Lindsey Leininger, Jenn Dowd, Lauren Hale, and Sandra Albrecht. We were soon also joined by the amazing Gretchen Peterson, our COO and the glue that holds us together — and a cadre of other volunteers and student employees. Since then, we’ve added many other collaborators including Sarah Coles.

People very often ask whether everyone on the team already knew one another. Most people knew someone else on the team, and there are a lot of connecting threads, but not everyone knew each other. It wasn’t a pre-existing group. Many of our connections come from time spent at various academic institutions over the years.

Malia and Alison shared an advisor at UCLA (and overlapped there for a short time). Malia and Lauren knew one another from RAND, where Lauren was a postdoc and Malia — before grad school — was a project manager. Alison, Shoshi, Ashley, and Aparna are all colleagues at Penn. Sandra, Lauren, Malia, Jenn, and sometimes Alison all attend a small professional meeting every year, the Population Association of America’s annual conference. Lindsey and Jenn knew one another from their time as RWJF fellows. Sandra, Jenn, Amanda, and Vicki were all at UM at the same time. None of us already knew Michelle, but when she wrote to say “I have a PhD in immunology from Penn and I’d like to volunteer” we said YES PLEASE. Sarah came to us through a professional connection to the American Academy of Family Physicians. It was supposed to be a one month guest spot, but we decided to keep her. Gretchen is Lindsey’s mom’s best friend.

Illustration of the overlapping institutions of the team members

I started doing a lot of press. A lot. Jelani Memory, founder of the small publishing house, A Kids Book About, reached out to me to ask about a fast-turnaround kids’ book. We workshopped the book in a day, and they released it as a free downloadable e-book at the end of that week. The last day that I went into my office on the UW-Madison campus was Thursday, March 12th. My kids’ schools shut down on March 13th. That night we had a party with our 6 closest friends, whose 6 children are our kids’ closest friends, all in the same school. My friend Kate baked me a cake that said “Pick Friends, Not Noses” in icing.

Pick friends not noses.

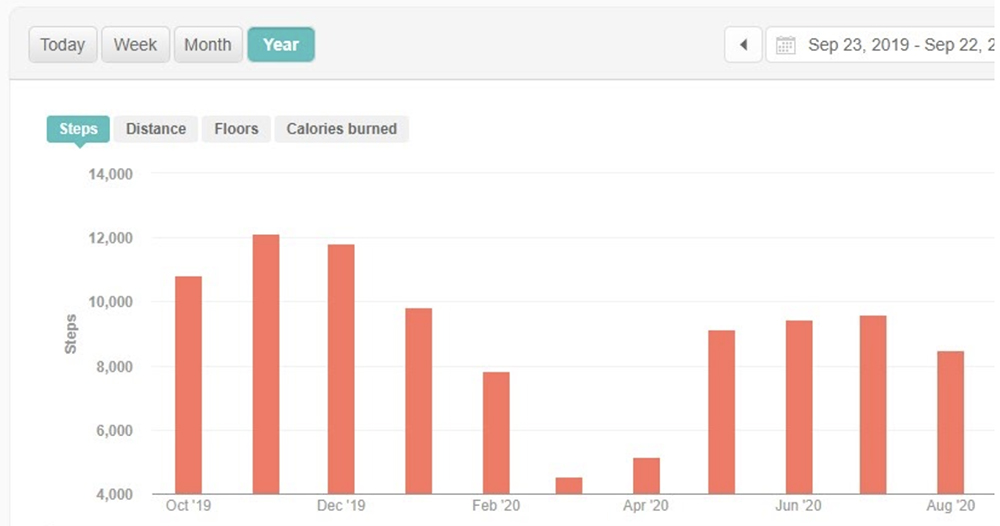

By this time, I was receiving literally dozens of requests every single day to answer people’s highly specific questions about their own risk situation. Lindsey coined the phrase “COVID Concierge” to describe this new role. Question: if you spend 30 minutes giving personally tailored advice to each one of 25 people each day, how quickly are your emotional and mental energy stores drained? I was putting in 15 hours behind my desk, 7 days a week. My Fitbit data for March and April tells the story better than I can.

My kids were supposed to be “virtually” doing kindergarten and 4th grade, but I utterly gave up on that enterprise. Our kids watched the entire backlog of My Little Pony Friendship is Magic episodes. All 9 seasons, plus the movie. My husband got laid off from his job, spent a couple of weeks panicking, and then started his own company–something he probably should have done a long time ago anyway, but maybe with more notice. Any “homeschooling” that occurred during this time can be entirely credited to dad. I broke a 9 month no-alcohol streak. I gained 15 lbs in a month. It was, to be honest, a pretty bad time all around.

I started noticing patterns. People are astonishingly bad at generalizing. You can tell someone “I think you should wipe off your Amazon boxes,” and they’ll say, “What about my mail?” You can say, “To be on the safe side, you should cancel sports practice,” and they’ll say, “Even soccer?” You can say, “I think you should cancel soccer,” and they’ll say, “What about softball?”

In mid- to late-March, we started noticing all sorts of experts from other fields arriving on the scene to comment on disease transmission and “help” epidemiology sort it all out. Computer engineers seemed especially prone to thinking they could pick up an education in infectious disease epi by reading some stuff on twitter (or writing some!). But we also had plenty of input from other fields. Overwhelmingly, those newly-minted infectious disease experts were white men. It was remarkable. In fact I remarked on it publicly, and often. I was ready to double down on the girl power behind our team.

The Dear Pandemic team started posting on a schedule of 2-3 posts a day, with each of us taking a couple of shifts a week. We had no leader. Everyone picked their own topic. Everyone wrote their own stuff. It was good. It was grounding. It was keeping me sane. It seemed like it was keeping our followers sane, too.

Today we are an interdisciplinary, all-girl team of doctorally trained researchers and clinicians with areas of expertise including nursing, mental health, demography, health policy, economics, family medicine, immunology, and epidemiology. We rely on an amazing team of volunteers, consultants, and student employees to help us get our message out.

We have posted hundreds of essays on how to live during a pandemic and done hundreds of interviews with the press. We’ve spent untold hours in our Slack workspace, backchanneling and learning from one another’s diverse disciplines and lived experiences. I don’t know what this year would have looked like without the team of people who make up Dear Pandemic. It doesn’t bear thinking about.

I remember an initial project team meeting where we laughed and got to know each other and discussed the idea of sunsetting Dear Pandemic by August 2020. In early April, we still expected there to be a rapid increase in testing capacity and then a success story of the United States detecting case clusters and doing outbreak suppression. We would flatten the curve and be done with this whole mess sometime in early summer 2020. We’d be getting back to “normal life.”

At this point, I think most of us recognize that there is no return. I’ve stopped leading with, “This isn’t my field,” because that’s no longer true. Now, I study pandemics, infodemiology, and applied science communications.

I have not started any of those sweaters.