A candid look at breast cancer risk

It’s time to shift the conversation about breast cancer risk and be candid about what we can and cannot control. We are bombarded by messages about everything we should be doing, or not doing, to avoid cancer. Mainstream media cranks out endless stories about cancer-causing chemicals in our food, coffee, water, beauty products, cookware, and more. Cancer education organizations nudge us to reduce our risk by exercising regularly, eating a healthy diet, avoiding smoking and alcohol, and so on. While it’s true that certain lifestyle choices can move the needle on cancer risk, this “empowering” message can be misleading and harmful when it ignores the broader risk landscape.

The uncomfortable truth about breast cancer is that our risk is shaped much more strongly by factors that we don’t control than factors that we can. This disease can affect all of us – not just people with a family history, or those who drink, smoke, and live a sedentary life. Providing a clearer picture of breast cancer risk can reduce self-blame while promoting important actions like screening and advocacy.

Imagine that your personal cancer risk barometer is a pot of pink paint. The darker the pink, the greater your breast cancer risk. Everyone is born with a white pot of paint. It’s not until our 30s that red paint starts to taint our pots. At this point, people assigned female at birth get a big splash of red paint every year and even bigger splashes as they move into their 50s, while people assigned male at birth get tiny drips. People with a strong family history get bigger splashes of red at an earlier age, reaching a vivid pink by midlife.

When we engage in behaviours that increase our risk (e.g. drinking alcohol daily) we add a little red paint. When we take preventative action (e.g. regularly exercising vigorously) we add a little white paint. These choices taint our paint’s hue but don’t transform it. Someone with a dark pink pot of paint can’t mute their shade to pale pink no matter how much they exercise, eat well, and avoid drinking or smoking.

Breast cancer experts estimate that we’d have roughly 25% fewer cases if everyone followed cancer prevention guidelines to a tee. Likewise, many breast cancer risk calculators don’t include lifestyle factors, and when they do, their impact is modest at best.

Risk factor that you can’t control: big splashes of paint

The most powerful non-modifiable risk factors dial up our breast cancer risk by double, triple, or more.

- Being born female. Breast cancer is about 100 times more common among women than men.

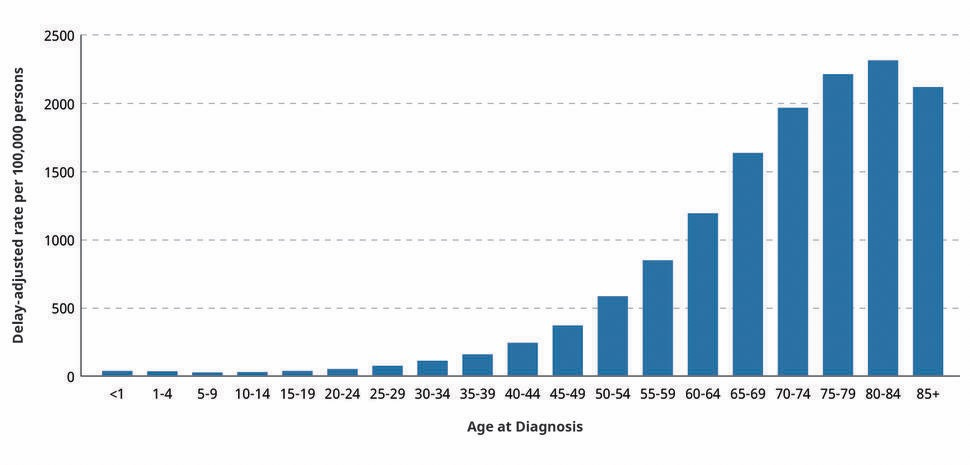

- Getting older. Over 80% of breast cancers are diagnosed after age 50. Average risk women are about five times more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer in their 50s than their 30s, and twice as likely in their 60s compared to their 40s.

- Genetic mutations. For people with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, the genes most commonly linked to breast cancer, the lifetime risk of breast cancer is about 7 times higher (13% for average risk compared to 50-85% for women with BRCA mutations). Inherited mutations in several other genes also contribute to breast cancer risk, but are less common.

Other risk factors that we can’t change include family history, personal cancer history, race, breast density, reproductive history (age of first and last period), radiation history, and more. Learn more from the American Cancer Society.

Risk factors that you can control: little drips of paint

The most powerful modifiable factors have a modest impact on breast cancer risk, dialing it up or down by 5-25%.

- Alcohol. Light drinking (around 1 drink per day) is associated with a roughly 5-10% risk increase.

- Exercise. Depending on the study we see a 10–25% lower breast cancer risk in the lowest versus highest exercisers.

- Body weight. Obesity and weight gain after menopause are associated with a 20-60% higher risk of breast cancer.

Hormonal medications (some birth control and menopausal hormone therapies) may also increase breast cancer risk, but these risks have been overblown and miscommunicated in the last few decades. This topic warrants a deeper discussion to unravel the confusion, controversy and nuance.

Other risk factors over which we have some control include having babies and breastfeeding (both are protective). Learn more from the American Cancer Society.

For those interested in learning more about menopausal hormone therapy, I implore you to watch out for misinformation and use credible resources like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and The Menopause Society. I also have selected expert interviews on my podcast, Get Real Health with Dr. Chana Davis. I’ve interviewed Dr. Carla DiGirolamo, a reproductive endocrinologist, and the authors of Estrogen Matters, medical oncologist Dr. Avrum Bluming and psychologist Dr. Carol Tavris. Tune into our chats on Apple Podcasts (Episodes 19,20, and 45) and Spotify (Episodes 19, 20, 45).

What else can you do?

We can’t completely prevent cancer, but we can take steps to reduce the toll it takes. Following screening guidelines, getting genetic testing, considering prophylactic surgery, and advocating for your healthcare can all support the best possible outcomes.

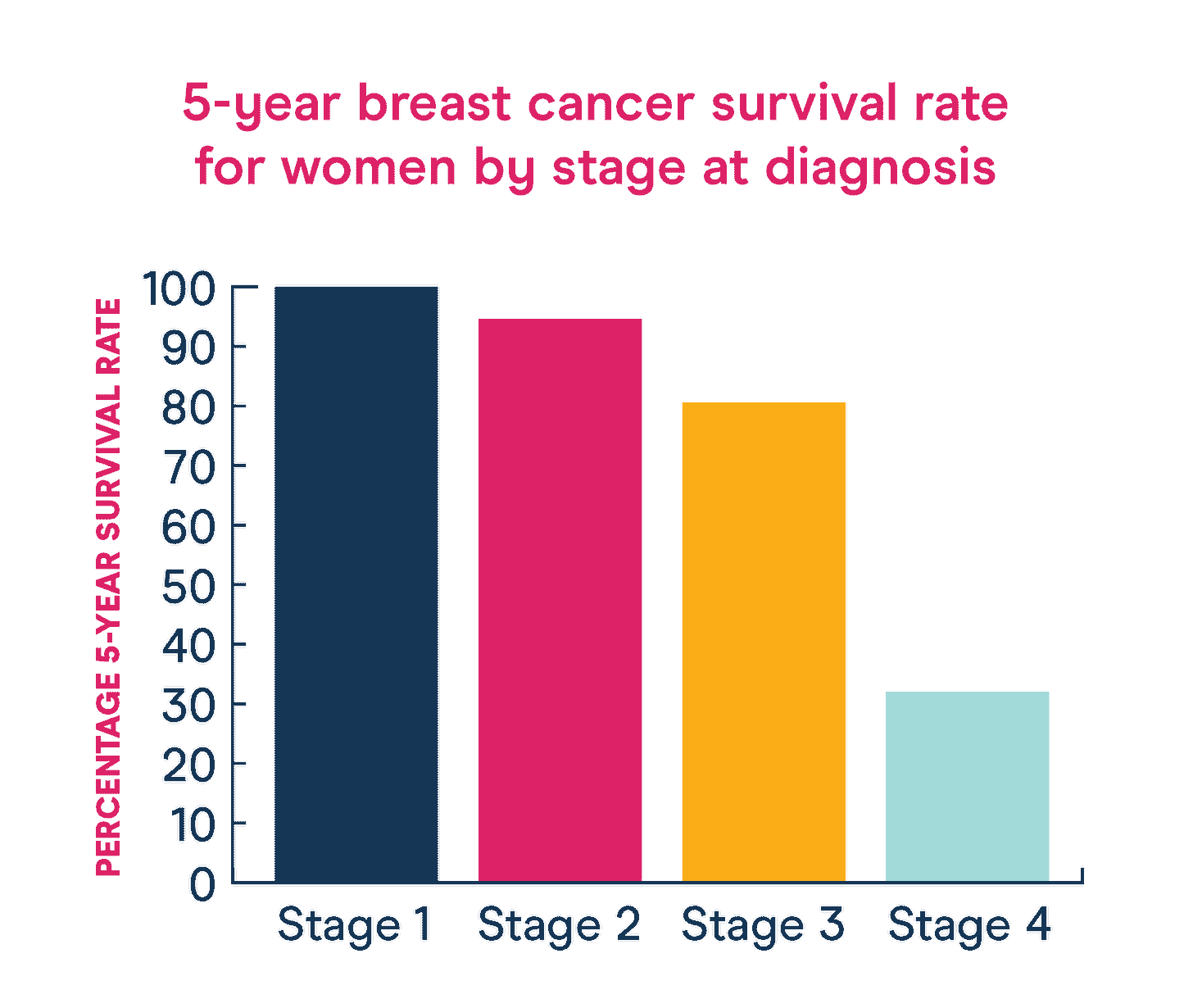

When we catch breast cancer before it spreads, it’s highly treatable and rarely kills (5-year survival rates exceed 99% for localized breast cancer). Screening mammograms (and related imaging tools) are invaluable for early detection. They are estimated to reduce breast cancer deaths by around 20%, though numbers vary from study to study. For women in their 40s (like me!), the balance of benefits versus risks is less favourable for screening mammograms, because cancer is far less common – which is why we don’t have alignment across expert bodies.

No discussion of screening mammography is complete without considering its serious limitations. The most common issue is false positives – mammograms often “catch” things that are not cancer. In fact, false positives are often more common than true positives (cancers), especially in lower-risk populations. Another important limitation is overdiagnosis – catching cancers that don’t need to be treated. Unfortunately, we can’t tell in advance whether or not a tumour can be left untreated. On the flip side, annual mammograms miss some lethal cancers (false negatives). Unfortunately, imaging tests are better at catching large, slow-growing lesions than small, aggressive tumours.

Monitoring our breasts can also be helpful, though guidelines are evolving as we better understand both the benefits and risks. Most medical experts no longer recommend routine self-exams in average-risk women because studies have shown that they don’t save lives and lead to many unnecessary biopsies (e.g. Canadian Task Force for Preventative Health, American Cancer Society, Cancer Research UK). Instead of routine self-exams, breast health experts suggest becoming familiar with how your breasts normally look and feel, and letting your doctor know about dramatic changes.

For people with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, genetic testing is a powerful tool. It can help you understand your risk level so that you can get screened appropriately and consider prophylactic surgery. It can also inform the likelihood that other family members are at increased risk.

Last, but not least, we can protect our health through self-advocacy. When healthcare systems are beyond their capacity, long wait times for diagnosis and treatment are the norm. At best, long waits cause anxiety and discomfort. At worst, they have serious health impacts. One friend had to wait several months to get treatment for her newly diagnosed breast cancer, which progressed while she was waiting. She would have waited even longer had she not been pushing hard to find a surgeon who could see her sooner. I wish that you didn’t have to be a “squeaky wheel” to get optimal healthcare, but this is the unfortunate reality for most of us.

Knowledge is power

When you realize that breast cancer strikes even the healthiest people, it shines a light on the other ways we can optimize our journey – through early detection and advocacy. Recognizing our limited control over breast cancer risk is also crucial for mental health in patients since agonizing self-blame is all too common.

In our podcast interview, Dr. Stephanie Graff, a breast cancer medical oncologist, mentioned that patients often ask her “Why did I get breast cancer?”. She told me that she sensed that patients were ultimately asking what they could have done differently, and that her response was: “You know you did nothing wrong, right?”. I want to add my voice to hers and remind you that much of our breast cancer risk is out of our hands – for better or for worse. Tune into our conversation on Apple or Spotify.

I want to leave you with a final thought on lifestyle choices: although they have only modest impacts on breast cancer risk, this doesn’t mean they don’t matter. The same behaviours that (modestly) reduce our risk of breast cancer also protect us from other common diseases, from cardiovascular disease to stroke to other cancers. I remain highly committed to stacking the odds in my favour through healthy living and encourage others to do the same.

On a personal note, I’m still in limbo about my suspicious breast lesion but my needle biopsy is finally booked. I’m feeling cautiously optimistic and reminding myself that false positives are more common than true positives in my risk group.

I hope that the knowledge you gained today serves you well on your own journey.

Yours in science and in heart,

Chana