Q: Like, how long does one need to inhale infectious aerosol to be infected? How long can the virus stay in the air indoors? Is there a risk of aerosol transmission outdoors?

A: This is your lucky day. An incredible team of scientists who study aerosol transmission of COVID-19 (including some we’ve cited here on Dear Pandemic, like Dr. Linsey Marr of Virginia Tech and Dr. Jose-Luis Jimenez of CU Boulder) have assembled an amazing “FAQs on Protecting Yourself from COVID-19 Aerosol Transmission” (link below!). They are updating them regularly as new evidence becomes available. The content is very thorough for the COVID-curious and also accessible for the lay public, with great illustrations!

Here’s a sampler from the 54 (!!) FAQs that echo questions you submitted to our Dear Pandemic question box. Thanks to this terrific aerosol team!

(Question #’s are keyed to the FAQ doc linked below.)

3.3. How long does one need to inhale infectious aerosol to be infected?

Catching a whiff of exhaled breath here or there is very unlikely to lead to infection. The amount of time you spend in close proximity or in a shared room with an infected person affects how much virus you actually inhale, which will dictate your risk of becoming infected. There is no clear amount of time as far as we know, but it would seem to be on the order of minutes.

The CDC says that 15 minutes of talking with an infectious person in close proximity is typically needed to get infected. However, that seems arbitrary to us and is not supported by evidence as far as we know. It can also give a false sense of security that a 5 or 10 minute interaction is safe because it is under the 15 min. threshold.

3.4. How long can the virus stay in the air indoors?

How long the virus stays in the air depends on the size of the droplet/aerosol that’s carrying it, as well as on the amount of clutter and air motion in the room. Virus has been found in tiny aerosols, smaller than 1 micron, and these can stay floating in the air for more than 12 hours, BUT these small aerosols will typically leave a building in the air faster than they settle to indoor surfaces.

How fast does air leave a room? It is a little complicated. Think about a cup of black coffee. How much milk do we have to add to the cup before we only taste milk? If we add one cup of milk to our cup of black coffee (allowing it to overflow) the result will still be a tan mixture. In fact, due to mixing it will be just two thirds milk. We would need to add three cups of milk to get our original black coffee cup to be 95% milk.

Indoor air behaves the same way. As outdoor air enters an indoor space it mixes with the air already indoors. So how long does it take to replace aerosol laden air from indoor spaces with outdoor air? In residences, 95% of the indoor air will likely be replaced with outdoor air in a time frame that ranges from 30 minutes to 10 hours. In public buildings, 95% replacement may take between 12 minutes to 2 hours. In a hospital, 95% replacement might take 5 minutes.

So how long a virus can stay in the air indoors is highly dependent upon the indoor environment.

4.1 Is there a risk of aerosol transmission outdoors?

All data show that outdoors is far safer than indoors, for the same activity and distance. But that does not mean that outdoors is 100% safe, and some cases of transmission (here and here) have been traced to outdoor conversations. Engaging in riskier activities outdoors may undo some of the benefits. Crowded outdoor locations, especially in more confined spaces (e.g. between two tall buildings) under low wind conditions and not in the sun, are the riskier ones. This is because there is less wind to disperse the virus-laden particles, and less UV to deactivate the virus.

The risk of transmission is much lower outside than inside because viruses that are released into the air can rapidly become diluted through the atmosphere. Again, think of the smoke analogy, if you are outdoors and you could inhale a lot of smoke if the people near you were smoking, then there is more risk. This virology professor at UMD thinks he was infected while waiting in line, while the wind was parallel to the line. Hard to prove, but plausible. But again, outdoors is much safer than indoors.

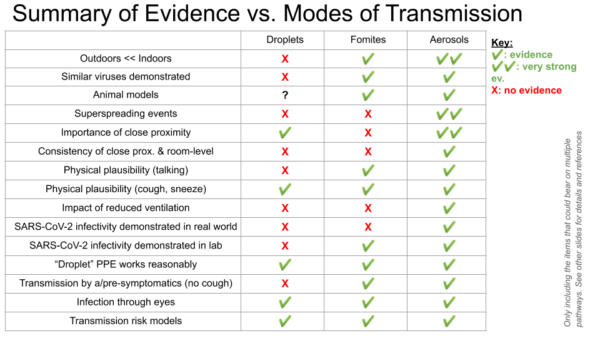

Image credit: Dr. Jose-Luis Jimenez of CU Boulder, in Summary of the Evidence For and Against the Routes of Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 https://tinyurl.com/aerosol-pros-cons. (also appears in the FAQ)