This is another in our new series Nerdy Notes: Science in Story & Verse.

In these posts, our Nerdy Girl scientists and clinicians will share personal stories, insights, poetry, and more. While these posts may be lighter in terms of numbers and figures, they will still be rooted in our tradition and commitment to providing accessible and trustworthy information.

Stay inspired, stay creative,

Those Nerdy Girls&+

Bad Brain: Navigating Medical School with a Brain Tumor

Navigating medical school with a benign brain tumor gave me perspective on the beauty in our fragility.

Two weeks before I was accepted into medical school, I found out I had a pituitary tumor. The pituitary is a small gland located at the base of the brain. I had some lab work done during my primary care appointment. A few weeks later, at my yearly gynecology appointment, the doctor looked through my labs quickly and asked if anyone had followed up about my hormone levels. I shook my head. “Maybe,” she said, perhaps too calmly, “You might want to follow up with an endocrinologist about that.”

I followed up immediately. About five minutes into the endocrinology appointment, I was told that I should get a brain MRI. “It’s probably fine,” she said. “But just in case.”

As someone long diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, there is one thing in this world that I am exceptionally good at: worrying. My worry is almost religious. If I worry enough about every bad thing that can possibly happen, then it won’t happen. So, I worried. Going into the MRI, I knew that the likelihood was that there would be a pituitary tumor. Like so many of us when we worry about our health, I turned to Google the night before and read everything I could find. Pituitary tumors are mostly benign, and they can be treated with medication to shrink them. However, whether or not the medication works depends on whether the tumor is producing hormones. If it doesn’t shrink, you can go in for surgery. It’s an endonasal surgery where they go up your nose. Recovery is just a few weeks. It’s fine, I tell myself resolutely. Really. I went through the information I had learned as the nurse prepared me for the MRI. The surgical success rates were good, but there is the possibility of a stroke.

I found more things to worry about as I stepped up to the MRI platform. My partner will probably dump me. I blinked as they snapped the cage over my head before they slid me into the machine. I guess I wouldn’t blame him, I decided magnanimously as the whirr of the machine cut through the classical music playing through my headphones. He didn’t sign up for brain surgery, after all. And if anything bad happened during surgery…well, he didn’t sign up for that either.

And so it went as I waited for the results of the scan. I thought, If I worry about it now, it will be fine. There won’t be a tumor. My boyfriend won’t dump me. The magic of worrying will save me from surgery.

But then the MRI results came back. I didn’t worry enough.

And then the email from my endocrinologist, “You should see a neurosurgeon.”

I named my tumor because it felt odd to not have some way to refer to it, a reminder of what can go wrong, a reminder that my body was malfunctioning. My partner held me while I cried (because, really, what else are you supposed to do if you find out you have a tumor?) and helped me call the neurosurgeon’s office.

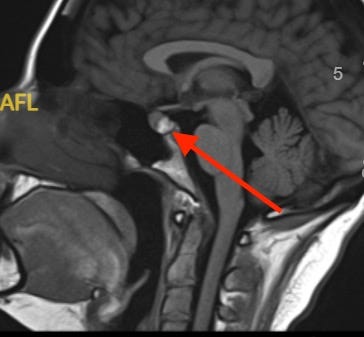

When I saw the neurosurgeon a week later, he was kind and optimistic. “You’re not special,” he seemed to say. “Tons of people have pituitary tumors and don’t even know. It’s not a big deal.” I wanted to reach across his desk and hug him. He said that as many as thirty percent of people have pituitary tumors that they never know about. He pointed to the image of my brain, bright on his computer screen. This is fine. I’m going to be fine. “Unless it grows, and really, it has almost an inch to grow before I’m concerned.”

Great! We aren’t worried. The plan is to check in every six months. The neurosurgeon has spoken, and if he’s not worried, I’m not worried.

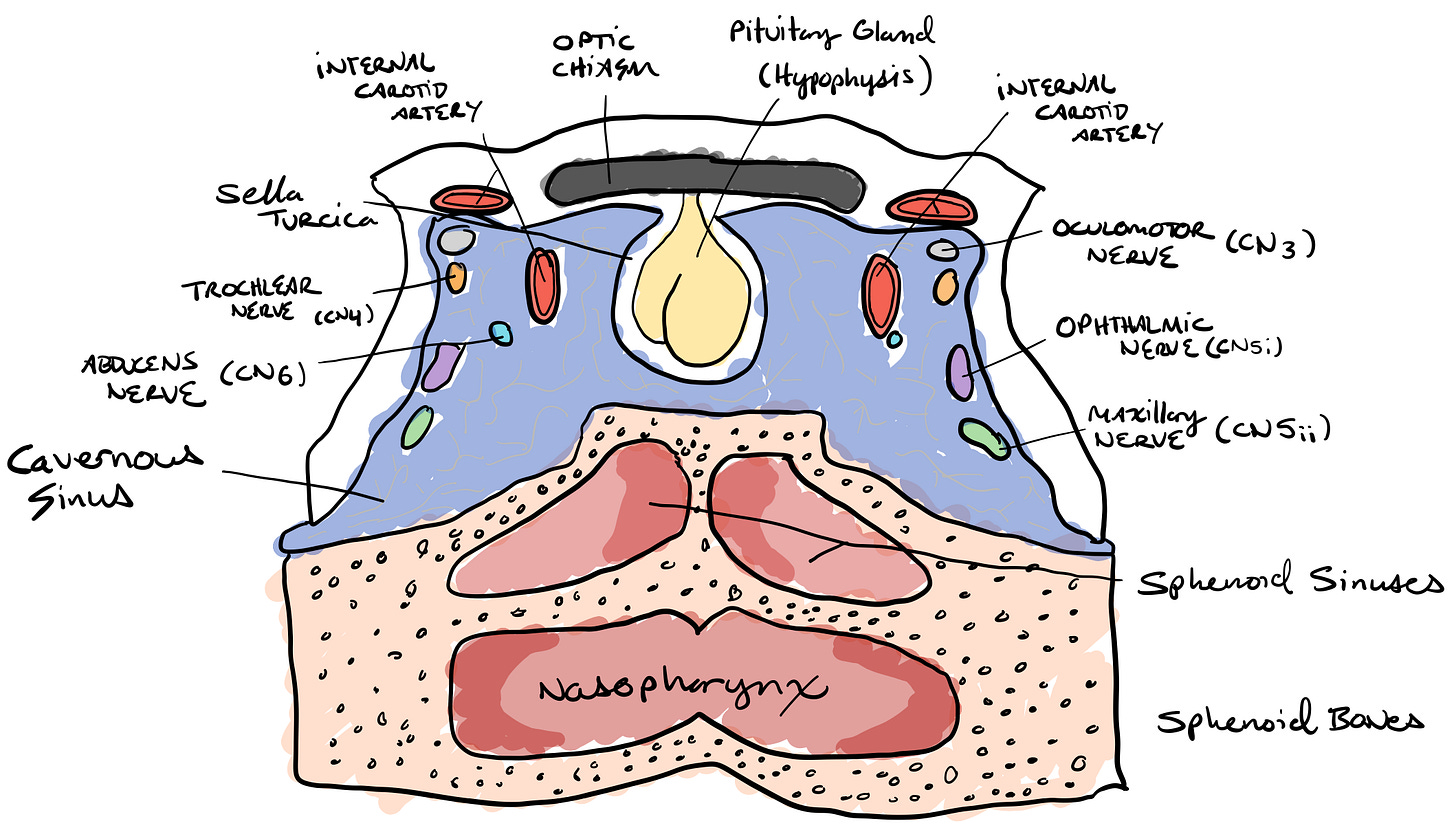

But then, according to my next MRI, six months later, it grew. Just a little bit. Instead of down, like it was supposed to, where it had so much space to stretch out, it started growing sideways into my cavernous sinus. Which, at first, seemed fine. A sinus is just an empty space in your body, I told myself. The cavernous sinus, I later learned, is a space approximately behind the top of your nose, where the very important internal carotid artery runs, along with the cranial nerves responsible for vision and eye movement.

[Illustration by E. Wish. You are looking at the pituitary gland from the top as if staring down into my skull.]

[My MRI – looking at my skull sideways. The red arrow points to the pituitary gland/tumor.]

I began medical school weeks later. I found myself replaying my neurosurgeon’s words in my head over and over. We’re fine. A little growth isn’t concerning just yet. Sometimes that happens.

I study. I dissect in the cadaver lab. I take exams. I push back my MRI a few more weeks. I occasionally worry that the stress headaches are some harbinger of tumor growth. But I mostly don’t think about it. My head is simply too full of new information.

And then, one day, sitting in class, looking at a PowerPoint slide about the internal carotid artery going through the cavernous sinus, I think about my stroke risk if I have to have surgery. The internal carotid artery branches into vessels that supply oxygen to a huge part of the brain. I see the diagram of all the cranial nerves that go through that sinus and think of all of the problems that come with disruption of those nerves. I silently chant the symptoms of cranial nerve lesions. It all sounds mixed up and meaningless in my mind as I am confronted with what is happening inside of me on the big screen of the lecture hall. Please, I whisper to no one. Please let it be okay.

The reality is, every single one of us is dealing with something. We all get scared, and we all worry. For the rest of my life, every once in a while, I have to check on the tumor. But I’ve decided I’m not scared of it anymore. If there’s anything medical school has taught me, it is this: we are all wonderfully, beautifully, incredibly fragile. Our bodies do their best to hold us together, but bones break and tendons rupture. If we’re lucky, we get old, and our eyesight goes, and our memory lapses. And that’s okay. It’s all part of being human. All we can do is be a little kinder to ourselves and the people around us because we only have so much time.

I often think of the skulls we looked at in anatomy lab. On the inside of the bone there are thin lines where arteries expanded and contracted against the inside of the skull for decades, molding the tissue to fit their path. Bone is living, it models and remodels itself, bending to the flow of blood, the pressure of those millions of red blood cells rushing by, leaving bony rivers inside of us, a gentle valley, shaped quietly to remind us we are alive.

Further reading: