TLDR; Many things impact infection risk, including vaccination status, prior exposures, genetics, and the specific details of one’s contact with infected people.

Even when conditions seem ideal for transmission, it’s not a done deal. This is why, if COVID comes to your home, it’s worth trying to limit spread. And sometimes, you just get lucky.

Even though it’s SUPER transmissible, we’ve all heard of what seem like unlikely escapes from COVID-19 infection – including long car rides or sleeping in the same bed with an infected person, but never testing positive. Are some people naturally immune? Previously infected but didn’t know it? Are the tests unreliable? What’s going on?!

This is a great question! First of all, let’s get one thing straight. Yes, it’s possible to remain uninfected when everyone around you has COVID. It doesn’t mean the tests were wrong. No test is perfect, but the tests we have for SARS-CoV-2 are pretty good. So how can this happen? Like a lot of science, the answer is both simple and really complicated.

Let’s start with simple. For a virus to transmit from one person to another, enough viral particles must be able to leave an infected person, get into the body of a susceptible person, and get past that person’s immune system. In other words, there’s a lot going on and sometimes not everything lines up for transmission to happen. In the biz, we call these things viral, host, and environmental factors. This just means what the virus is like, what we’re like, and what is going on around us. And let’s not forget the importance of timing.

🦠 Because SARS-CoV-2 is a dynamic, new pathogen, you’ll hear a lot about viral factors in the news. The Omicron variant, for example, is way more transmissible than other COVID-19 variants. Transmissibility is a viral factor impacted by both the virus’s ability to escape our immune protections and also how easily it enters human cells and makes copies of itself once there.

🤒 We hear a bit less about host factors, but they are important for this question. One thing that varies from person to person is our behavior. Some people are always talking or singing while others are often quiet. But our immune systems are probably the root of many differences in susceptibility to COVID-19 infection. Each person’s immune response to an infectious challenge is shaped by their prior exposures, their genes, and even their medications or stress level. Over the millennia, we humans have evolved a pretty neat immune system. Our immune cells are constantly patrolling our bodies, scanning for threats, and learning. Vaccination and prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 make a big difference, priming our immune systems to fight back the next time we’re exposed. Each of us gets different immune features from our moms and dads, but on top of that our immune cells have a special system to introduce extra variation so that they can recognize new pathogens that neither we nor our parents have seen before. (Sound interesting? Check out this video for more about the amazing variability of the human immune system.)

This immune variability impacts how easy it is for a virus to infect us and what happens after that. That’s why one person may get very sick while another of the same age has a just tickle in their throat. Our immune systems also play a role in how much virus we release while we’re infected and for how long.

🌳 But before you decide that you or a loved one are one of the fortunate few with a COVID-proof immune system, remember that environmental factors (meaning what’s happening outside the body) and timing play an important role too. To infect a new person, viral particles have to get from the infectious person to the susceptible person. A lot can impact that, even in situations where we intuitively feel like effective contact is a done deal. We all know by now that SARS-CoV-2 transmission is less likely outdoors where there is a lower chance of breathing shared air. But even indoors or in close quarters, the exact conditions of contact between people will impact transmission.

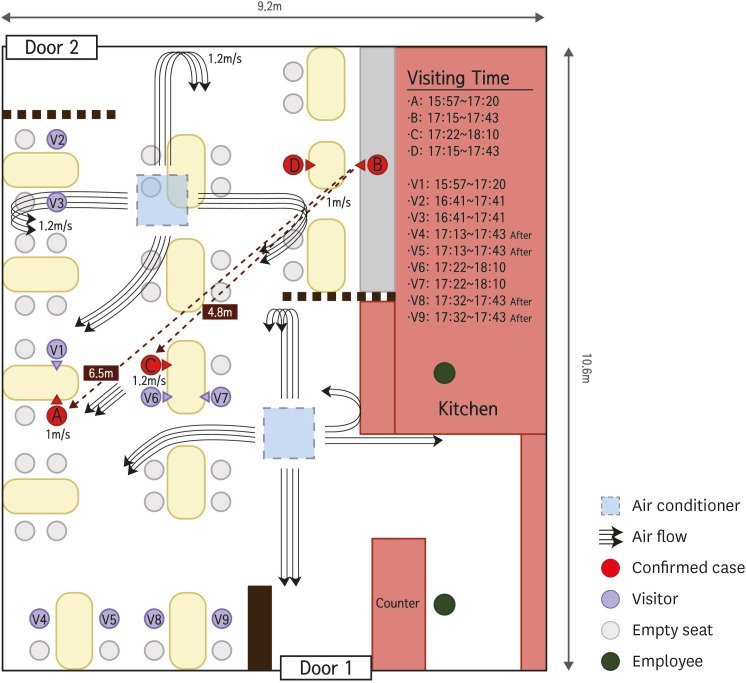

🌬️ Investigations of COVID-19 outbreaks, for example, have shown that in some settings the direction of airflow can be critical to who gets infected. The figure below shows an outbreak in a restaurant in Korea where person B infected person A, who was 6.5 meters away in the path of air currents caused by the room’s ventilation system, while people who were sitting physically closer to person B were not infected. (Note this was 2020 so the virus has gotten more transmissible since then). These little chance circumstances can make all the difference.

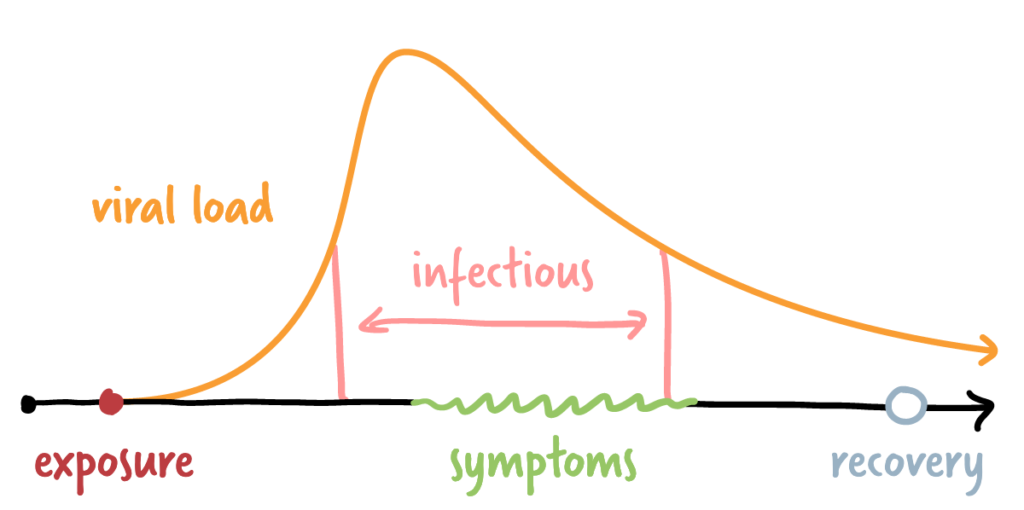

⏲️ And one last thing. Timing matters. We make generalizations about the infectious period for COVID-19 and we usually talk about days, but an infected person’s ability to transmit the virus increases rapidly over a short time on the order of hours. The diagram below shows SARS-CoV-2 viral load over the course of an infection. It’s a summary based on numerous studies of viral load in infected people. The very steep increase early in the infection shows that, although it’s not an on/off switch, a person can quickly go from being not infectious to being pretty infectious. In most circumstances, a person can’t know for sure when their own infectious period truly began. Sometimes, the virus just misses its window.

⬇️ BOTTOM LINE:

There are probably a *few* people who may never catch COVID-19 because of their biology. But most people who’ve been exposed and escaped infection were likely either protected by their immunity from vaccination and/or prior infection or “lucky” that the air currents, infectious dose, or another random factor was in their favor that day. As SARS-CoV-2 continues to spread, the chances of this “luck” running out increase, so continue to take precautions around infected loved ones!

Thanks to Guest Nerd Dr. Jessica Williams-Nguyen for tackling this tough question!

Links:

Washington Post: “The lucky few to never get coronavirus could teach us more about it”

DP post in the epidemiological “triad” from way back in June 2020

Sources for Figures: